When I was a toddler, I loved science. Each and everyday I would come up to my mother and ask her to read books to me, not fairytales nor fables, but entries from encyclopedias and magazines the likes of National Geographic. My mother recalled those days with both joy and horror. As she was glad that her son was deeply interested in academics, yet dreaded having to stay up until midnight just to dictate endless articles until I would fall asleep. With the addition of the endless questions that would undoubtably come up the next morning.

Of course, as I grew older I learned to read by myself. And in these days as well, my love for science never wavered. Especially in the field of biology. My days were filled with paragraphs upon paragraphs that involved mammals, reptiles, plants, and the ever-popular subject with children, dinosaurs. I didn’t loathe reading, much to the surprise of my childhood classmates and teachers. Instead I welcomed all opportunities to do so. When I was punished for being disruptive or tardy and sent to the library for detention, I would scour the shelves to look for anything interesting, and actually hated the prospect of getting sent back to the classrooms and playgrounds.

Yet my passion for the natural sciences waned over the years. Partly because of personal laziness, but also due to the approach my educators applied when it came to teaching. I won’t deny the fact that I wasn’t a model student. When I was still enamored by science, any other subject I considered to be unimportant. Language, art, history classes those I lumped in the same category I regularly dismissed, resulting in quite unsatisfactory grades. But then I threw biology, chemistry, physics, all the fields that once enraptured me into the same grouping of what I deemed to be “boring.” The first part of my academic underperformance can easily be blamed on my personal failings, but the latter, not so much.

To expand the scope of this article beyond my life story, we will begin discussing the failings of the Indonesian educational system. Why this expansion is necessary is because Indonesia’s approach to education led students akin to myself to be disinterested in topics they were previously captivated by. And we need to find out how these instances of sudden disinterest came to be, should we wish for the youth of Indonesia to perform better academically not just on the national, but also international level.

The reasoning behind the abrupt apathy to academics, as implied in the above paragraph, is related primarily to how the system itself regards Indonesian pupils. After years of spending time within the system, and speaking to those who hold little praise for Indonesia’s education—including school teachers and university lecturers—it’s rather simple to determine the system’s failings: It doesn’t allow for subjects to be intriguing, it actively hinders either creative or critical thinking, and rote memorization grants better grades than comprehension, giving the system the image of being akin to a factory. Explanations are indeed in order, as these claims are fairly harsh.

Now why would I say that Indonesia’s educational system prevents the many fields of study from becoming intriguing? In other words, causing students to not want to dig deeper into the subjects they’re currently learning and simply sticking to the explanations they’re given without doubt. From the experiences I’ve underwent, as well as those that have been describe to me by friends and family, and unpleasant image begins to draw itself.

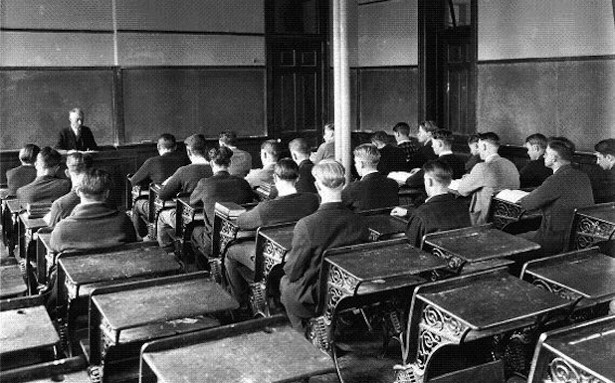

When Indonesian pupils enter their classrooms, they are not expected to inquire. Lessons are written on whiteboards or at times projected, the letters on textbooks are recited and sometimes sprinkled with minor elucidations should the students be lucky enough to be granted an active teacher. Yet all the while, these schoolboys and schoolgirls sit, listen, and take notes without—as the educators instruct—making a sound.

At times, the students are permitted to ask about the current topic of discussion. But not to further the lesson by inciting more in-depth explanations nor debates within the classroom, or god-forbid point out the errors found in the teacher’s or textbook’s accounts. Rather the questions serve more as requests from the students for the teacher to reiterate his or her words, should the students in question fail to grasp the concepts laid out before them. There are no other functions observable in querying educators. In fact, in certain schools—whose names I will avoid mentioning for fear of defamation charges—these pleas of help are sufficient grounds for reprimands. Since the students who voiced them are often perceived as either “slow” or “disturbances to the classroom.”

At this point, we can discern a clear problem: Students cannot truly learn, in the sense of completely understanding their lessons, without asking questions. How is a pupil supposed to comprehend topics as complicated as a human being’s right to live, when the explanation amounts to nothing more than “because they’re allowed to.” Replies which eliminate any possibility for detailed discussion, and a sudden halting of a student’s desire to further explore complex subjects. Altering the concept of learning into no more than memorization, which I will speak of later on in the text.

We, the students, educators, and national curriculum should always encourage questions, discussions and debates in the classroom. For each of these acts promote curiosity in the minds of students. Compelling them to read, watch, and listen to whatever content that could expand their comprehension on the countless subjects in academics. Furthermore, this spurring of curiosity could induce a thirst for creativity and critical thinking.

The concept of introducing creativity and critical thinking into academics is more commonly found in the Western world. And perhaps their dominance in Western academic culture is why they are rather under-appreciated in Eastern countries the likes of Indonesia. Yet under-appreciation does not make these approaches to learning any less significant. In actuality, perhaps these methods are more necessary than at any other point in Indonesia’s academic history.

One of the most common complaints I encounter from my university lecturers, is that a great number of freshmen are unable to write essays. Sure they might be able to explain theories, cases, and so on, but for some reason providing basic explanations is the most that many of them can do. I do not believe that their failure to conjure up worthwhile essays—ones that introduce concepts, criticize theories, and so on—is because they lack the capacity to write. Rather, their shortcomings originate mainly from how assignments are given and how these works should be completed during their school years. From the elementary to the high-school levels.

Both the school-works and home-works of Indonesian schools are quite dull. In the sense that they ask simply for answers that could be found from text-books, without urging the students to formulate their own opinions. While such a method could work for certain cases, when even the writing of essays require pupils to not stray from the material provided by the school, nor research the contributions of other scholars on the topic at hand, an issue arises. The students are trained to follow whatever texts and lectures they are given, and are urged to subdue their own ability and willingness to think creatively and critically. Reducing them into overtly similar products, rolled off the production lines of factories disguised as academic institutions. An obvious deviation from the fundamental purpose of schools.

Indonesian students are forced to be memorizers, not learners, but sponges of information; unquestioning, unthinking humans, who are constantly in pursuit of better grades instead of greater understanding. How could Indonesians then, as a people, ever hope to achieve a greater stature in the international level of academia, when schools actively discourage students from actually thinking? Is it any wonder then, that the wealthiest of Indonesians choose to send their children to schools in foreign lands, and that their offsprings are viewed as cleverer than the Indonesians who chose to learn in their homeland? There is no mystery here. The wealthy have simply realized that for their children to fulfill their academic potential, Indonesian schools need to be avoided.

For all the reasons I’ve listed above, and the explanations that accompany them, I hope that I have managed to adequately illustrate why Indonesia’s approach to education needs to be revised. How to do so, can be done merely by avoiding the pitfalls that have been listen in the previous paragraphs. Failure to heed this call for reform would result in more and more generations of apathetic students. Who attend their classes for the sake of grades. Who, when challenged to think, will struggle as they have been stripped of that right by the educational system. For Indonesian schools do not seek to produce the brightest pupils. They are rather akin to factories, breeding humans who are forged to see and understand the world in an overtly similar, unquestioning manner.

Indonesia is a nation blessed with countless bright minds, yet we have failed them by not providing the proper tools with which they could hone their cognitive abilities.